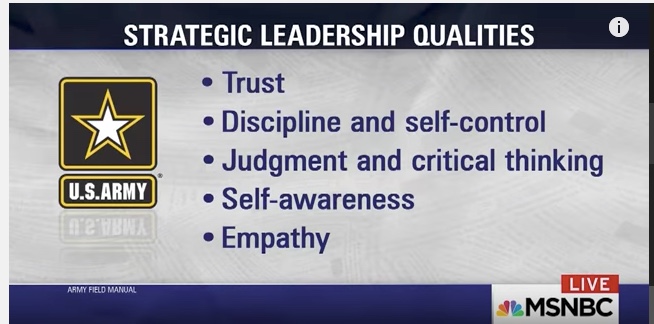

Five Criteria for Judging a Leader’s Fundamental Capacity to Carry out his Responsibilities and Duties

- Trust,

- Judgment/Critical Thinking,

- Discipline and Self-Control

- Self-Awareness

- Empathy

How do we recognize a person who can be entrusted with the fate of a nation, a corporation, a university or any enterprise where actions and decisions have critical impact? There are five critical fundamental capacities a leader in a position of great responsibility must have: trust, judgment, discipline, self-awareness and empathy. Together they constitute a model of an emotionally mature adult with the necessary temperament and cognitive capacity to allow him or her to function at the highest level required of someone who has enormous responsibility.

Great leadership certainly requires additional qualities and capabilities–vision, daring, the capacity to inspire, discernment, creativity and so on. But first, a leader must demonstrate the fundamentals enumerated in this checklist. Without them he or she cannot carry out the duties required of someone in a position of high office.

This model of the fundamentals required of a leader is based on the principles of mature, high level mental functioning developed in the fields of psychology, psychiatry and psychoanalysis over the last 100 years. I discovered that the Army Field Manual Leader Development fm6_22 follows the same path and arrives at the same destination. The scorecard I’ve developed is distilled from that Army Manual. It’s virtue is that it does not require specialized knowledge such as a background in Psychiatric evaluation. It allows a leader’s mental capacity to lead to be determined by any reasonably observant and thoughtful person using common sense. The scorecard can also be used by leaders to assess their own strengths and weaknesses and plan a program for improvement of their personal leadership capacity. In fact, one of the Army Field Manual’s prime missions is to assist leaders in developing their leadership abilities.

An earlier and somewhat briefer version of this scorecard was published as an Op-Ed in the LA Times on June 16, 2017 “Is Trump mentally fit to be President? Let’s consult the Army’s field manual on leadership”

*Trust. According to the Army, trust is fundamental to the functioning of a team or alliance in any setting: “Leaders shape the ethical climate of their organization while developing the trust and relationships that enable proper leadership.” A leader who is deficient in the capacity for trust makes little effort to support others, may be isolated and aloof, may be apathetic about discrimination, allows distrustful behaviors to persist among team members, makes unrealistic promises and focuses on self-promotion.

As a psychiatrist I’ve observed that an individual lacking in trust habitually blames others when problems arise, avoids taking responsibility and consistently feels beleaguered and unfairly treated.

*Discipline and self-control. The manual requires that a leader demonstrate control over his behavior and align his behavior with core Army values: “Loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage.” The disciplined leader does not have emotional outbursts or act impulsively, and he maintains composure in stressful or adverse situations. Without discipline and self-control, a leader may not be able to resist temptation, to stay focused despite distractions, to avoid impulsive action or to think before jumping to a conclusion. The leader who fails to demonstrate discipline reacts “viscerally or angrily when receiving bad news or conflicting information,” and he “allows personal emotions to drive decisions or guide responses to emotionally charged situations.”

Discipline means having the ability to forego an immediate reward for a later, greater outcome.

In psychiatry, we talk about “filters” — neurologic braking systems that enable us to appropriately inhibit our speech and actions even when disturbing thoughts or powerful emotions are present. Discipline and self-control require that an individual has a robust working filter, so that he doesn’t say or do everything that comes to mind.

*Judgment and critical thinking. Judgment and critical thinking are complex, high-level mental functions that include the abilities to discriminate, assess, plan, decide, anticipate, prioritize and compare. A leader with the capacity for critical thinking “seeks to obtain the most thorough and accurate understanding possible,” and he anticipates “first, second and third consequences of multiple courses of action.” A leader deficient in judgment and strategic thinking demonstrates rigid and inflexible thinking. His thinking is not innovative

The ability to think critically and strategically is a necessary precondition for good judgment. “Sound judgment is dependent on the ability to organize thoughts logically, to plan ahead, to understand cause and effect and most importantly to anticipate the consequences of an action,” according to the Army manual.

Problem solving is dependent on thinking and judgment, so these capacities can be evaluated by observing how the leader responds to a crisis. Most importantly, can he considers the long-term consequences of his actions.

Because it is absolutely fundamental to effective leadership, the AFM expands at length on the specifics involved in critical and strategic thinking. This leadership capacity involves actively seeing different points of view, considering alternative explanations and looking at the big picture. Thinking, speech and ideas should be deliberate and well-organized. Assessments should include looking for gaps in information and seeking to have them filled, while looking for inconsistencies. The leader “keeps reasoning separate from self-esteem”. Planning is careful, thoughtful and based on complete information and the synthesis of the divergent views and alternative explanations which should be actively sought. Priorities are clear and well thought out.

Helpfully, the AFM gives a vivid description of the behaviors of a leader deficient in judgment and strategic thinking. That leader fails to consider alternative explanations or courses of action. He fails to consider second and third consequences of an action. He oversimplifies, cannot distinguish the critical elements in a given situation and is unable to handle multiple lines of thought simultaneously. He Is hasty in prioritization and planning. He cannot or does not “articulate the evidence and thought process leading to decisions”.

*Self-awareness. Self-awareness requires the capacity to reflect and an interest in doing so. “Self-aware leaders know themselves, including their traits, feelings, and behaviors,” the manual says. “They employ self-understanding and recognize their effect on others.” When a leader lacks self-awareness, the manual notes, he “unfairly blames subordinates when failures are experienced” and “rejects or lacks interest in feedback.”

Self-awareness creates a desire to understand: motives, how feelings are affecting judgment, how one is impacting others, how one is viewed by others. The AFM describes the necessity of the capacity for “metacognition” which is the ability to think about thinking, to observe and regulate one’s thoughts.

This capacity enables a leader to put the following essential functions into effect in all his decision making: Actively consider what he knows and doesn’t know; maintain awareness of his thinking process and its strengths and weaknesses; be alert to his emotions and their impact on his thinking; act tactfully; make accurate assessments of social cues; and listen to and let the views and feelings of others have an impact on him.

*Empathy. Perhaps surprisingly, the field manual repeatedly stresses the importance of empathy as an essential attribute for Army leadership.

A good leader “demonstrates an understanding of another person’s point of view” and “identifies with others’ feelings and emotions.” The manual’s description of inadequacy in this area: “Shows a lack of concern for others’ emotional distress,” is indifferent to their pain and “displays an inability to take another’s perspective.”

Empathy is required for an effective leader because it is this capacity that allows him to accurately understand another person’s intent and to be able to foresee the impact of his actions on others. The Army guide states that the empathic leader can be identified because he is respectful of others, cares about subordinates and creates a positive work environment. A person who is deficient in this capacity He focuses solely on his own needs without considering those of others. He de-humanizes the enemy.

As a psychiatrist, I’ll add another dimension to empathy. It’s not enough to understand how another person feels – the best dictators are adept at sensing other people’s’ vulnerabilities and exploiting them. A leader also must care about the impact of his words and actions on others. The AFM description of inadequacy in this dimension: “Exhibits resistance or limited perspective on the needs of others. Words and actions communicate a lack of understanding or indifference.”

June 26, 2017

Copyright Prudence Gourguechon 2017